When we sin (the operative word being “when”) we instinctively feel a judicial impulse that that someone must pay a price for our wrong-doing. Deep down we really don’t believe that anyone should get off “scot-free.” What we need to decide is who is going to pay the price for our transgression.

MY TREAT

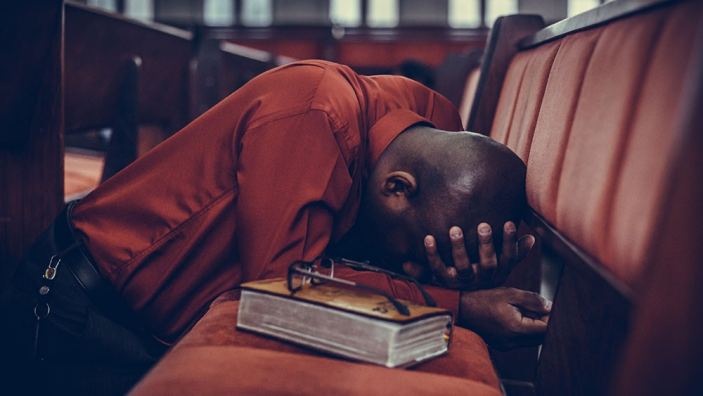

“I am pig swill.” This is one of the terms I use when beating myself up for having fallen into the same trap of sin, yet again. There’s no copyright on the phrase so feel free to use it.

Not cognitively, but in essence, what I’m doing is crucifying myself for the sin I’ve comitted. Yes, what Jesus did was nice, but I’m going to take this one on myself. Someone must pay and rightfully it should be me so I pound myself for my stupidity.

YOU PAY

“You, you made me sin.” That “you” could be any person, Satan, heck, it could even be God. But either way someone needs to take the fall for the sin I’ve just committed and I’ll be darned if it’s going to be me.

NO HARM, NO FOUL

“Now that you mention it, I’m not sure that really was a sin.” Recognize it? It’s called justification. And as the word implies we decide to make a judgment over and against our conscience, declaring that what we did was actually right, or at least not that wrong. Why go to the effort? Because someone must pay for sin, unless of course there is no sin to be paid for, and that’s what we’re shooting for in this approach: to eliminate the offense.

I HAD TO

“I couldn’t help myself, it’s just my personality.” Let’s call this rationalizing, which is equivalent to the courtroom plea of insanity. What I’m saying here is, “Yes, it was sin but I didn’t have the moral capacity to say ‘no.’” My personality was such, and circumstances were such, that I could do no other than what I did.

The effectiveness of this strategy lies in how good you are at convincing yourself that it’s really not your fault. I’m pretty gullible so I usually believe me.

We are all brilliant lawyers but try as we might the judge, God, is not hearing any of it. It’s true that when we feel the conviction of sin, someone needs to pay the penalty and suffer the consequences, but they already have – 2,000 years ago – so our pleabargaining was never needed. What is needed is to confess our sin:

“If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness.” (1 John 1:9)

Confession is the acknowledgment and personal application of Christ’s death on the cross to our specific sin. Confession is an expression of faith which results in our experiencing what God has already done for us through the death of his Son.

Christ died for each and every one of our sins; confession is the vehicle through which we experience the cleansing, mercy, and forgiveness of Jesus’ sacrifice.

The Greek word for “confession” literally means “to say the same thing” or “to agree with.” This sheds some light on what is involved in confession.

In prayer, we first agree with God that we have sinned (this stands in contrast to the alternatives we looked at). Second, we agree with God that Christ’s death paid for that specific sin. And last, we agree with God to turn away from that sin and ask him to empower us to do so (this is called repentance).

This is so critical to understand, and so critical to maintaining fellowship with God that I want to state it again, so that you read it again:

In prayer we, first, agree with God that we have sinned. Second, we agree with God that Christ’s death paid for that specific sin. And last, we agree with God to turn away from that sin and ask him to empower us to do so (this is called repentance).

HOW OFTEN SHOULD WE CONFESS OUR SIN?

About every 90 seconds. That’s a joke: you seemed to be getting a little too intense about the topic, and I felt I should loosen you up a bit. You confess sin whenever God makes you aware of it throughout the day. It’s also not a bad idea to comb your mind whenever you have opportunity for an extended time of prayer.

BUT I DON’T FEEL FORGIVEN

If it makes you feel better, this is something everyone struggles with. I’ve often wondered which makes God sadder: the sin itself, or not receiving the forgiveness he has purchased for us. I wouldn’t be surprised if sometimes it turned out to be the later: one is a moral failure, the other a failure of faith: one heightens our need for Jesus’ death, the other empties it of its power.

Our relationship with God is not effected by sin. By virtue of our new birth, we will forever be his children and he will always be our Father. But as with any relationship, sin does hinder fellowship. If you’ve confessed your sin, then your guilt has been forgiven and your fellowship with God has been completely restored. Yet for some sins – those ground-in, tough-to-get-out stains – you may find that feelings of guilt linger. To help in feeling forgiven, try the following two exercises:

1. Write out on a piece of paper every sin you’ve committed that comes to mind. Next, write out across the list the words of 1 John 1:9:

“If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness.”

Then thank God, rip up the list, and throw it away— preferably where it cannot be found and posted on the Internet.

2. Although we can’t see God, sometimes others can model his forgiveness to us. This is why Scripture tells us, “Confess your sins to each other so that you may be healed” (James 5:16). Who could you connect with on a weekly basis to share your struggles prayer requests, and sin?

The critical things to remember about confession are: You should confess sin throughout the day as soon as God makes you aware of it. Confession restores fellowship, not your relationship (that never changes). The three components of confession are agreeing with God that you sinned (don’t justify it), agreeing that Christ’s death paid for that sin, and agreeing to turn away from that sin, asking God to empower you to do so.

©2025 LMT. All Rights Reserved.